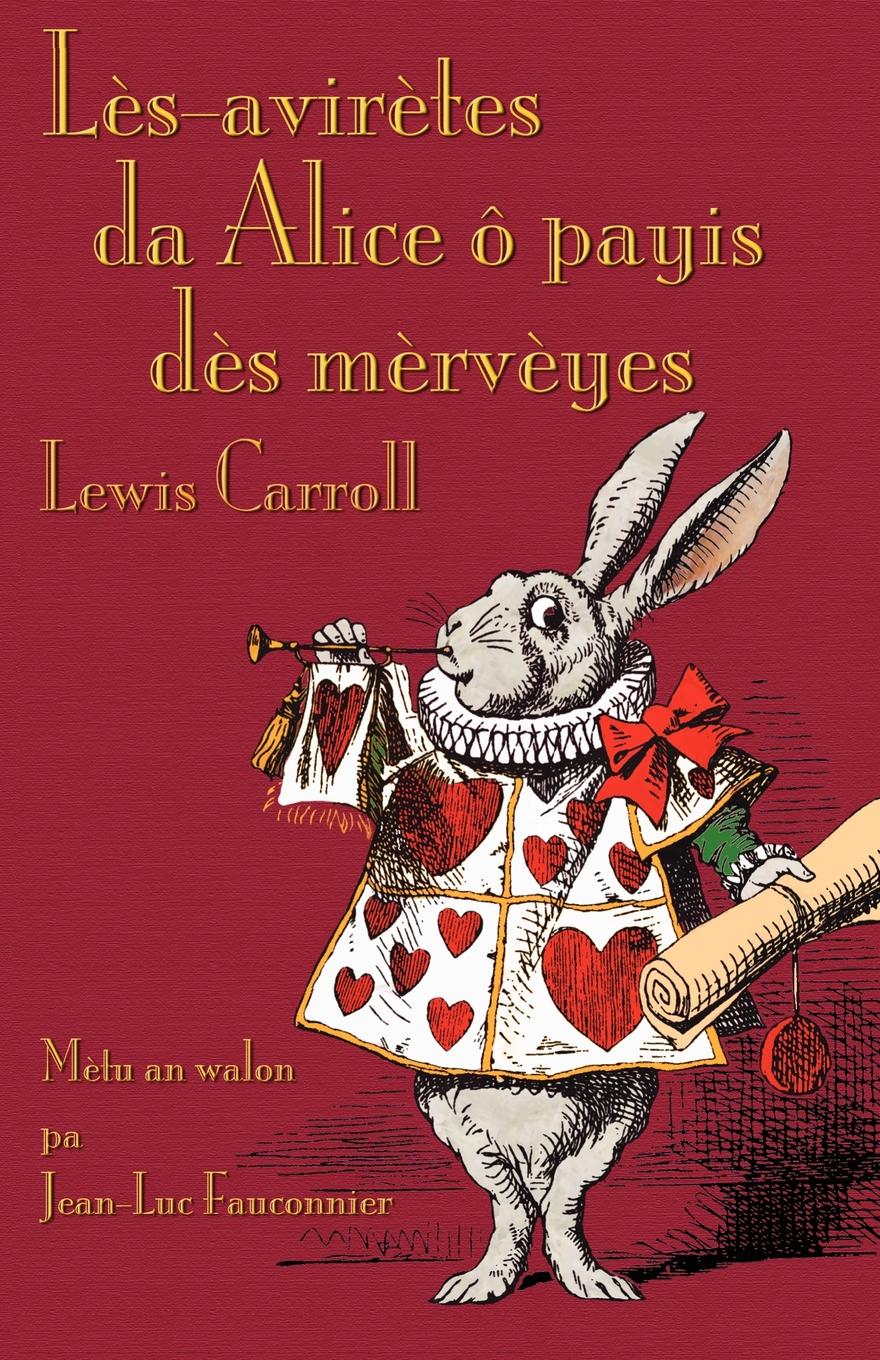

Lès-avirètes da Alice ô payis dès mèrvèyes

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in Walloon

By Lewis Carroll, translated into Walloon by Jean-Luc Fauconnier

First edition, 2012. Illustrations by John Tenniel. Cathair na Mart: Evertype. ISBN 978-1-78201-005-0 (paperback), price: €12.95, £10.95, $15.95.Click on the book cover on the right to order this book from Amazon.co.uk!

Or if you are in North America, order the book from Amazon.com!

| “In that direction,” the Cat said, waving its right paw around, “lives a Hatter: and in that direction,” waving the other paw, “lives a March Hare. Visit either you like: they’re both mad.” | « Di ç’ costè la, » dit-st-i l’ Tchat, an fèyant in djèsse toûrnant avou s’ pate, « vike in Tchap’lî, èt di ç’ costè la, » a-t-i fét avou l’ôte pate, « dimeure èl Lîve di Mârs´. Alèz-è vîr èl cén qu’ vos voûrèz ; is sont djondus tous lès deûs. » | |

| “But I don’t want to go among mad people,” Alice remarked. | « Mins dji n’ vou nén dalér mon dès djondus, » a-t-èle èrmârquè Alice. | |

| “Oh, you ca’n’t help that,” said the Cat: “we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.” | « Ô, gn’a nén moyén dè vûdî, » dit-st-i l’ Tchat : « nos ’stons tèrtous djondus roci. Dji sû djondu, vos ’stèz djondûwe. » | |

| “How do you know I’m mad?” said Alice. | « Comint ç’ qui vos savèz qui dj’ sû djondûwe ? » dit-st-èle Alice. | |

| “You must be,” said the Cat, “or you wouldn't have come here.” | « Vos d’vèz l’yèsse, » dit-st-i l’ Tchat, « ou bén vos n’ârîz nén v’nu roci. » | |

|

||

| Lewis Carroll is the pen-name for Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, who was a lecturer of mathematics at Christ Church, Oxford. Dodgson started the telling of this tale on July 4, 1862 during a rowing boat tour on the Thames River at Oxford. Pastor Robinson Duckworth and three girls were members of the party: Alice Liddell, the ten-year old daughter of the dean of Christ Church, and her sisters Lorina, aged thirteen, and Edith, eight years of age. The poem at the beginning of the story states that the threesome urged Dodgson to tell them a story. And so he set out to present the first version of the tale, admittedly with some initial reluctance. Now and then, within the broader tale, reference is made to all five of the boat party; the story first appeared in print in 1865. | Lewis Carroll, c’èst l’èspot di scrîjeû da Charles Ludwidje Dodgson qui f’yeut l’ classe di matématiques al Christ Church d’Oxford. Dodgson a comincî a racontér ç’n-istwêre ci adon qu’i f’yeut ène pourmwin·nâde a bârquète su l’ Tamîse, a Oxford, avou trwès djon·nes couméres: Alice Liddell, èl fîye du dwèyin dèl Christ Church èt sès deûs cheurs, Lorina, tréze ans, èyèt Edith qui d’aveut wit´. Èl powème qu’èst ci ô cominç’mint du lîve raconte qui cès trwès couméres la ont soyi Dodgson pou qu’i lieû raconte ène istwêre. Èt c’è-st-insi qu’il-a présinté l’ preumî vûdâdje di ç’n-istwêre la, ène miyète a malvô, d’jeut-i. Toudis è-st-i qui dins ci scrijâdje la on d’visse dès céns qui f’yît l’ pourmwin·nâde a bârquète; l’istwêre a stî impriméye pou l’ preumî côp an 1865. | |

| One might wonder why I spent time translating Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland into Walloon. After all, everyone who speaks Walloon also knows French. For this reason, some people will pretend that it’s a waste of time and effort to translate into Walloon. | On poûreut s’ dimandér pouqwè ç’ qu’on-a passè s’ tins a r’mète an walon Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland ? Lès djins qui d’vis’nut an walon, is conèch’nut ètou l’ francés èt c’èst d’abôrd ès´ donér dèl pwène pou rén qu’i-gn-a dès céns qui vos prétind’ront. | |

| Let’s just say it straight out: I have translated that book into our language to show that it was possible to do it, and also to demonstrate that Walloon is by no means a lower-class language that is just used for joking, though it is a language still despised by many. I should add that Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland has been translated into many languages and that, logically, it had to be translated into ours too. | Dijons l’ platèzak, on-a mètu ç’ lîve la dins no pârlâdje pou moustrér qu’ c’ît possibe èt qui l’ walon, çu n’èst nén in lingâdje qui n’ chève qu’a racontér dès quéntes, in lingâdje qu’i-gn-a co branmint dès céns qui fèy’nut dès pûtes dissus. On rajout’ra ètou, qu’Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland a stî r’mètu dins-ène contrèmasse di lingâdjes èt qu’il-èsteut rèquis qu’èl walon eûche ès´ place, li ètou, dins l’ filéye. | |

| Walloon derives from Latin, like its cognates of the oïl cluster (including French). It is spoken in Wallonia, a part of southern Belgium, in the part of Belgium where French is the official language and that is called Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles; in this Fédération, the regional languages—Langues régionales endogènes—Champenois, Lorrain, Picard, and Walloon, have the good fortune to enjoy an official recognition since the year 1991, and so they can be defended openly and they can flourish more easily. | Èl walon, i vént du latin come sès cous´ dèl famîye d’oïl èy’ on l’ divisse an Walonîye, in boukèt dèl Bèljique qu’èst dins l’ sûd du payis, dins l’ pârtîye dèl Bèljique èyu ç’ qui l’ lingâdje oficièl c’èst l’ francès èt qu’on lome Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles; lôvô, lès pârlâdjes réjionâls—langues régionales endogènes—come èl champènwès, èl lorin, èl picârd èyèt l’ walon, is-ont l’ chance d’awè ène èrcon’chance oficiéle dispûs 1991. Insi, is poul’nut yèsse disfindus sins qu’on-eûche a l’ fé a muchète èy’ is poul’nut mompliyi pus ôjî’mint. | |

| As with many regional languages, there are many internal differences within Walloon, from one town to the next, from one village to another. Nevertheless it can be said that there are only four major varieties of Walloon: the eastern variety (or Liégeois), the central variety (or Namurois), the western variety, and the southern variety. | Come branmint dès pârlâdjes réjionâls, i-gn-a branmint dès diférinces dins l’ walon èt çoula, d’ène comune a l’ôte, d’in vilâdje a l’ôte; mins, on pout quand l’ minme dîre qu’i-gn-a quate grandes cougnes di walon: èl cén du l’vant (on dit pus râde èl lidjwès), èl cén du mitan (on dit pus râde èl namurwès), èl cén du coûtchant èyèt l’ cén du sûd. | |

| This translation was made in western Walloon, the one used in the Charleroi area. This area has always been a very industrial one: coalmines, glassworks, rolling mills. It is an area where the working-class formerly spoke only Walloon at work. Those workers originated from all over the area. They gradually created a common working language, a Walloon koine. My translation has been written in that common variety. Previously, the first three chapters had been translated into Walloon in the Atelier wallon of the Université du Temps disponible de la Province de Hainaut. | Èç traducsion ci a stî scrite an walon du coûtchant, èl cén dèl réjion di Châlèrwè. C’è-st-ène réjion qu’i-gn-a toudis yeû branmint dès-industrîyes—tchèrbonâdjes, vèr’rîyes, laminwêrs—èyu ç’ qui dins l’ tins, lès-ouvrîs, su leû b’sogne, is n’ d’visît rén qu’an walon, dès-ouvrîs qui v’nît di tous lès quate cwins dèl réjion èt qu’ont mètu a dalâdje, pyane a pyane, ène koinè; c’èst djustumint dins ç’ koinè la qu’on-a scrît l’ traducsion. Lès trwès preumîs chapites ont d’ayeûrs èstî r’mètus an walon dins l’Atelier wallon di l’Université du Temps disponible de la Province de Hainaut. | |

| To write Walloon, we are fortunate enough to have at our disposal a spelling system which was created by Jules Feller (1859–1940). If one uses it, one is able to write any variety of Walloon (and also other languages of the oïl cluster) nearly the way they are pronounced. | Pou scrîre èl walon, on-a dèl chance d’awè in sistème qu’a stî èmantchi pas Jules Feller (1859–1940); s’on l’ chût, on pout scrîre toutes lès cougnes di walon (èt co d’s-ôtes linguâdjes d’oïl) quasimint come on lès dit. | |

| One might believe it is not an easy task to put English words into a popular language like Walloon, but, at the end of the day, I found it to be a very pleasant challenge. | Gn’a pont d’ doute qui ç’ n’èst ôjî di r’mète di l’anglès dins-in pârlâdje du peûpe come èl walon, mins ô pârfén, ç’a stî in pléjant dèfi. | |

| Wallonia, of course, is not near to the sea, and consequently Walloon has rather few words with which to name the marine fauna. Consequently, I had to borrow several words from French, like omârd ‘lobster’, sole ‘sole’, foque ‘seal’. I had to cheat a little over the word whiting, which I translated èrin (herring) because the latter is very well known to us and because it looks a bit like a whiting. Traduttore, traditore… | Bén seûr, èl Walonîye n’èst nén asto dèl mér´ èy’ an walon, gn’a nén ène masse di mots pou lomér lès bièsses qui vik’nut dins ç’ grande basse la; du côp, on-a stî oblidji d’ dalér qwé saquants mots dins l’ francès, dès mots come omârd, sole, foque. On-a d’vu agonér ène miyète avou l’ whiting qui nos-avons batiji èrin, herring, paç’ qui c’è-st-in pèchon qu’èst bén conu amon nos-ôtes èt qui r’chène ène miyète au whiting. Traduttore, traditore... | |

| It is worth saying, however, that it has been sometimes difficult to adapt in Walloon Lewis Carroll’s witty word associations. Sometimes it was nearly impossible to translate them exactly, so that “cheating” became necessary. | Dijons quand l’ minme qui pa côps, on-a yeû saquants rûjes avou lès djeus qu’ Lewis Carroll a l’ pléji d’ fé avou lès mots. Mwints côps, c’èst quasimint impossibe di lès rinde tafèt’mint èy’ adon, i fôt fé ène miyète du tréte. | |

| I won’t bore the readers of this Foreword by explaining how I managed to translate all the jokes and puns satisfactorily. One good example will do—that of the Mock Turtle. Mock Turtle was rendered in Walloon by Tortûwe Grogne. Nobody eats turtle soup in Wallonia, but we are very fond of a dish which is made with small pieces of calf’s head, a dish that we call “dèl grogne”. This is the reason why I named that strange animal in this way. | I n’èst rèquis d’ soyi lès lîjeûs an-asprouvant d’ moustrér comint ç’ qu’on parvént a tapér filét; fuchons contint avou in boun-ègzimpe, li cén dèl Mock Turtle. Èl Mock Turtle a stî rindûwe an walon pa Tortûwe Grogne. On n’ mindje pont d’ soupe di tortûwe an Walonîye, mins on mindje vol’tî in plat qu’èst fét avou dès p’tits boukèts d’ tièsse di via, in plat qu’on lome dèl grogne; èt v’la pouqwè qu’ c’è-st-insi qu’on-a batiji ç’ drole di bièsse la. | |

| Finally we can say that after I succeeded in translating the English text with much effort, I enjoyed it greatly and came to realize that Lewis Carroll was a truly exceptional writer. | Tout contè, tout rabatu, on pout bén dîre qui l’ côp qu’on-a rèyussi a mète èl pîce ô trô après-awè branmint drânè èt spéculè èt bén, on pout dîre qui c’è-st-a ç’ momint la qu’on-a l’ pus d’ pléji èt qu’on s’ rint conte ètou qu’ Lewis Carroll, c’ît in fèl èscrîjeû. | |

|

Jean-Luc Fauconnier Châtelet 2012 |

Jean-Luc Fauconnier Châtelet 2012 |

|